SIREN UPDATE: A CONVERSATION WITH METRO COUNCIL REP DAVE ROSENBERG

Many of you remember our frustration with the current siren system. We vented (cough) more than a few times about it on Twitter and wrote a tl;dr position paper (below) about sirens in the context of the November 18, 2017 tornadoes. It’s now spring and here we are in the middle of tornado season, so I thought we should check in with the City Councilman who initiated the political process of modernizing Metro’s sires, Dave Rosenberg.

NSW: Who are you, what part of the city do you represent, and are you the hero who sponsored legislation with the Metro City Council to address the siren issue?

Dave: I’m the Councilman for Metro Council District 35, which covers much of the greater Bellevue area. I’ve been working with the Office of Emergency Management and the Mayor’s Office of Resilience with the support of many of my colleagues to modernize our tornado warning sirens.

NSW: What’s involved in the process, where are we with it, and what exactly are you trying to do with the sirens?

Dave: First, we needed to identify exactly what issues we were needed to solve to protect public safety. It’s no secret that there’s a lot of frustration with Nashville’s tornado sirens. We on the Metro Council hear it a lot. A tornado warning on Percy Priest Lake triggers warning sirens in Bellevue, where it’s sunny, or a tornado warning in Ridgetop triggers warning sirens in Antioch, where it’s a garden variety rain shower. Those false alarms breed complacency and that’s dangerous. We want folks to recognize that a tornado siren means you’re in danger and you need to take action. It’s confusing when the National Weather Service and local media say there’s no tornado warning in one part of Metro, but our old system still has all sirens going off. OEM has done a great job of managing the system we have in place to protect public safety, but technology has evolved and we have opportunities to do more. We need to equip OEM to modernize.

We had lengthy conversations about how to move forward, with the main options being a) breaking the county into zones and only triggering sirens that could be heard in those zones, and b) getting even more precise by using the National Weather Service’s warning polygons and only triggering sirens that can be heard within those warning polygons. We ultimately settled on (b) because it will be quicker for OEM to activate and will offer even fewer false alarms.

Next, OEM did a lot of research to determine exactly what costs implementation would include. And we learned that some of the current equipment is reaching its end of life, so we’d need to spend some money soon anyway.

That’s where we are now. We’ll need to secure funding in this year’s capital spending plan, which will be a collaborative process between Mayor Briley and his team and the Metro Council, particularly Budget & Finance Committee Chair Tanaka Vercher. An allocation of $542,500 will cover all electronics and batteries in our 93 siren control cabinets along with two new control points with polygonal alerting capability at the OEM Operations Center. If we can get those funds, Metro will be able to get started.

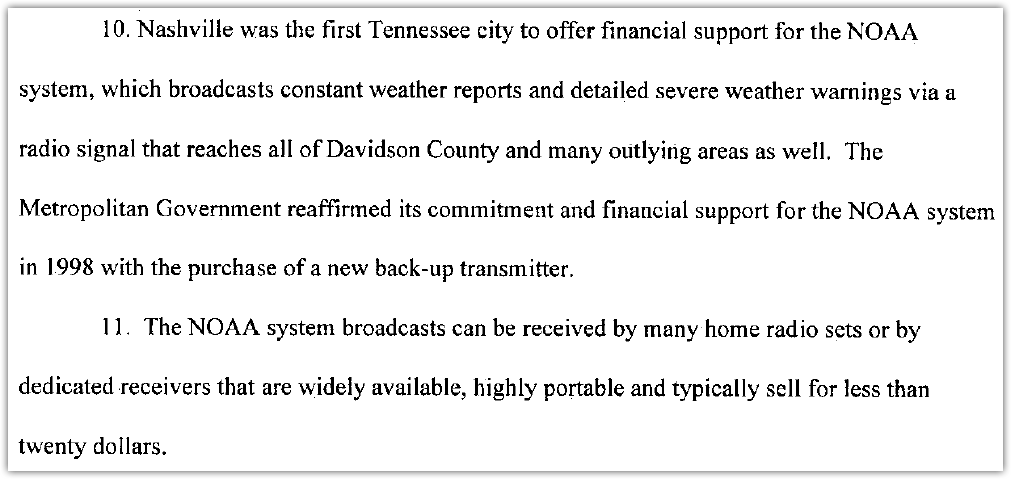

NSW: When will we know whether we can get those funds? What’s the next step?

Dave: The capital spending plan will probably be filed late this summer. Metro Council will debate that plan, make any needed changes, vote, and send it to Mayor Briley for his signature.

The most immediate step is encouraging support for funding this modernization. If you’re so inclined, you can encourage Mayor Briley, your district council member, and the at-large council members to advocate for moving this forward.

NSW: How do we contact council members? And who were the co-sponsors on the resolution moving the siren issue through the legislative process?

Dave: Council members are listed at https://www.nashville.gov/Metro-Council/Metro-Council-Members.aspx …. If you don’t know who your district council member is, there’s a form on that page that allows you to find out using your address.

We haven’t had any substantive legislation on the sirens. We unanimously passed a resolution (http://www.nashville.gov/Metro-Clerk/Legislative/Resolutions/Details/fc01a928-815a-40c8-a9d5-8eebf570b50f/2015-2019/RS2018-1037.aspx…) asking OEM to look into the feasibility of modernization, but that was really just an effort to ensure we didn’t let time slip away.

There is widespread support on the Council for upgrading, as you’d expect. We passed around a survey asking whether members preferred the current system or the proposed system, and it came back 23-2 in favor of modernization.

NSW: Excellent. Thanks for your work. We’re hoping we can modernize our system the way Oklahoma City and other tornado-prone cities have. It’s great to see the council hearing the needs of the people and responding so they can equip OEM with what they need to best serve the public. Thanks for answering these emails, and we’ll check back in a few months to see how it’s going.

Dave: Thank you for your support of this effort and all you do, not only to keep us all weather-aware during events at all hours but also to help spread understanding of the issues surrounding our community’s always-interesting weather. Tornado siren modernization is a worthy endeavor, second only to the regular distribution of West Wing GIFs, and your focus on both has been very helpful.

End of the conversation. Below is our case for siren reform.

THE CASE FOR SIREN REFORM IN METRO

If you take nothing else from this: Outdoor tornado warning sirens serve a limited purpose:

- they’re only supposed to be heard outdoors,

- they are not made to alert those inside, and

- they should not be your primary tornado warning source.

- Get a NOAA weather radio. Get a wake-me-up and wow-that’s-loud warning app.

Have multiple reliable ways to get tornado warnings. Do not rely only on sirens.

Below I argue Metro Nashville should at least study, and at best change, its policy of sounding all 93 of its sirens when a Tornado Warning has been issued for any portion of Davidson County. Instead, sirens should only sound for those inside the warning polygon.

Sirens Were Silent During The 1998 Nashville Tornado

In the 1960s, Nashville (with some federal money) installed less than 20 sirens when we feared communists would attack us. These were Cold War Sirens, part of a defense “air raid” siren system referred to as “CDS” (I assume that meant Civil Defense System).

Those Cold Warn/CDS sirens were silent as the Nashville tornado approached Centennial Park on the afternoon of April 16, 1998. There, Memphis resident and Vanderbilt ROTC student Kevin Longinetti was with his classmates. Tornado winds knocked down a tree, which struck Kevin. He died as a result.

Those at Centennial Park weren’t the only people outside and unaware. Channel 5’s video, looking out at James Robertson Parkway, shows the tornadic supercell approach while people walk down the street going about their day, seemingly unaware, walking casually and without alarm (until it got really, really close).

There was no siren there to alert them.

Could they have seen the tornado coming?

Probably not. Many Tennessee tornadoes are wrapped in, and obscured by, rain. Hills, trees, and buildings block view of the horizon. Our tornadoes frequently have low cloud bases, meaning they don’t tower majestically like tornadoes you see on Discovery Channel, on YouTube, and in movies like Twister and Sharknado. And, not all our tornadoes are backlit by daylight. We lead the U.S. in percentage of tornadoes occurring at night (45.8%). No matter the time of day, it’s unlikely you can see it coming, and if you wait until you hear the tornado’s roar, it’s already too late to take cover.

I wasn’t in Centennial Park on the afternoon of April 16, 1998, but I’m willing to bet good money if you looked west from there, from downtown, or from countless other places in Nashville, you could not tell that inside that approaching giant low cloud was a tornado. Even those in a tall building with a really good look at it weren’t really sure what exactly that was.

The Lawsuit

So why weren’t the Cold War/CDS sirens blaring on April 16, 1998? Kevin’s mother asked that question. She sued Metro for not sounding the Cold War sirens to alert those at Centennial Park — her son among them — of the approaching tornado.

Metro’s response to the lawsuit explained why the sirens had been deactivated.

“[T]he very high costs associated with maintaining or replacing the aging system; the reduced threat of air raids resulting from the winding down of the Cold War; the fact that energy-efficient construction methods such as installation of storm windows and insulation in homes and businesses greatly reduced the audibility of sirens indoors; and the fact that CDS’s coverage did not include the areas into which the City of Nashville had grown in the 20 years since the siren was installed.”

(Affidavit of Jim Bowden, para. 8, Slepicka v Metro, Davidson County 6th Circuit Court, No. 99C-1041).

Metro argued they were out of the tornado-alerting business, at least for outdoor sirens. Metro argued they had fallen in line with the National Weather Service’s warning method. Metro filed this affidavit:

How was NWS going to alert everyone? Weather radio. Remember, this was 1998.

(Affidavit of Jim Bowden, para. 9-11, Slepicka v Metro, Davidson County 6th Circuit Court, No. 99C-1041; if you’re wondering, the Court dismissed the lawsuit. The quick reason is that the law does not allow government agencies to have liability for failure to provide hazardous weather warnings. For you lawyers out there, the Order granting Metro’s motion for summary judgment cited the public duty doctrine, the discretionary function exception to the Tennessee Governmental Tort Liability Act, and the absence of proximate causation.)

So, why am I bringing up this lawsuit? Two reasons.

First, the lawsuit illustrates why we need an outdoor warning system. You’re probably aware I have been critical of Metro’s Office of Emergency Management’s (OEM) current siren policy, but let me be clear: I am not tossing rocks at OEM. I think I can say, safely, we agree an outdoor warning system makes sense. We don’t want another fatality or serious injury. We owe that much to Kevin, his grieving mother, and his family. And we owe it to each other. We are a community of musicians, students, health nuts, goat yogas, sports nuts, cyclists, crane operators, boaters, unicylers, motorcyclers, coaches, players, you name it, we do it outside. Safety is my #1 priority, too. What we have here is a disagreement about what’s best.

Second, the lawsuit reflects an irony — Metro defended itself in Court by saying it adopted the NWS warning model, yet today Metro’s siren policy confuses the public by contradicting the message from the NWS. This confusion at best delays response times and at worst causes people to ignore sirens and warnings altogether. As I wrote in 2015, and recently quoted by the Scene, Metro sirens and the NWS are “two members of a band reading off different sheets of music, and the song sounds terrible.”

It’s Not 1998 Anymore

We are much better detecting tornadoes now compared to 1998. Since that lawsuit, there have been advancements in radar technology to assist forecasters in issuing warnings. As in, seriously good advancements.

- The radar scans the skies more often. Radar isn’t “live.” Radar illustrates still images of what’s in the air (rain, wind, etc). In 1998, radar scans came every 5-6 minutes. Today we can get a new low-level scan every 60-90 seconds. That’s 4 to 5 times more information that we got 20 years ago.

- Radar detects rotation at a higher resolution now than it did in 1998. We can identify tornado debris on radar to confirm a tornado has occurred and is likely ongoing. No way we could do that in 1998.

- We know so much more about tornadoes now. Research has translated into actual, practical advancements in the field. The software is better. The training is better. The forecasters and warning decisionmakers are better. We have not figured it all out (the QLCS problem is discussed below), but the weather enterprise is warning tornadoes better today than it did in 1998.

- There’s a better network of storm spotters providing “ground truth” to assist warning decisions. Your #tSpotter reports are part of that.

Advancements better identify the strongest tornadoes. The probability of detecting an EF-2 or stronger tornado on radar is very, very high. That wasn’t true in 1998.

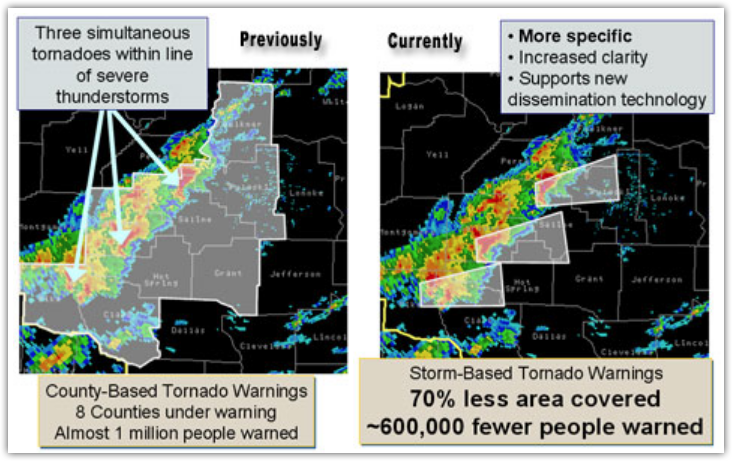

County-Based Warnings Ended in 2007

Before October 1, 2007, if any part of a tornado-producing storm touched any part of your county, the NWS issued a Tornado Warning for the entire county. This old system sent people to shelter who did not need to get to shelter, causing them to not believe the warnings they were getting. It was a bad system. People resented the unnecessary interruption in their day. Tornado detection was improving. It was time to end the overwarning era.

This report, published by NOAA (NWS is part of NOAA) in March 2007, concluded NWS should abandon the system of county-based overwarnings in favor of a storm-based warnings. This was implemented October 1, 2007.

This new (current) system of “Storm-Based Warnings [threat-based polygon warnings], are essential to effectively warn for severe weather. Storm-Based Warnings show the specific meteorological or hydrological threat area and are not restricted to geopolitical boundaries. By focusing on the true threat area, warning polygons will improve NWS warning accuracy and quality.”

Advancements in Warning Technology

In 1998, alerts could come from air-raid sirens or a NOAA weather radio, and maybe a scary sound on your TV. That was it.

Today, access to media and alerts are at an all-time high. WEA alerts — the thing that makes your phone freak out — are used by mobile phone carriers. Social media and apps distribute information and alerts. Most have a mobile phone in a purse or a pocket, making the warning system personal and portable.

This new technology works off the NWS storm-based/polygon-based system, not the only county-based system. So when NWS issues the warnings, phone alerts follow the NWS system. TV meteorologists follow NWS warnings. Apps use NWS alerts. Everyone’s in line, except Metro’s tornado sirens.

Metro’s Tornado Warning Policy is the Old System

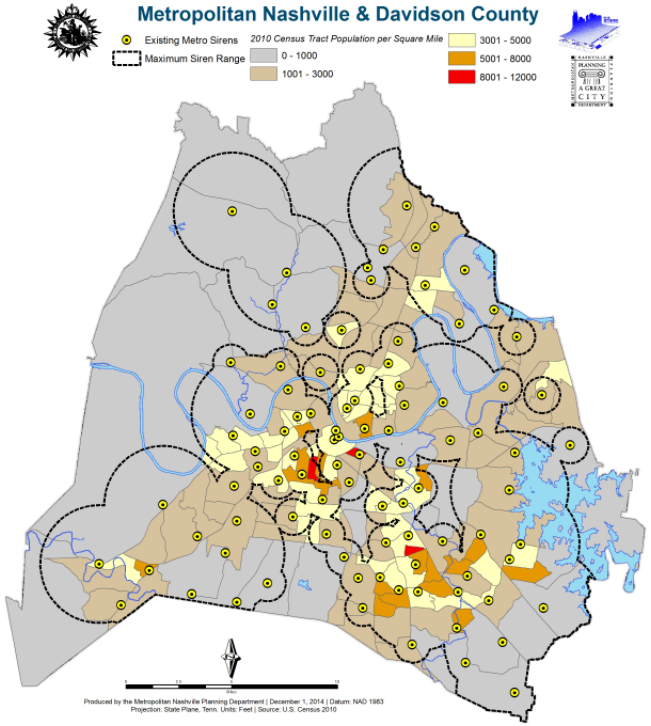

Metro’s website says our current “Metro Tornado Warning System . . . began with a federal grant in 2002, and has become better, bigger and broader. Between late February and the end of April 2013, 20 new sites were added, going from 73 to 93 locations countywide. Each siren is located in public gathering places selected by city planners on the basis of outdoor population and population density.”

The sirens themselves are pretty good. I’m glad we have them. Metro has done a good job keeping them working.

But, when do they go off? Officially, simply stated on its website, “The Tornado Warning Siren system is to help those in outdoor areas be aware that a tornado warning has been issued for any portion of the county. ”

That’s my issue: “any portion of the county.” That’s the legacy system, what NWS did before October 1, 2007.

Metro’s policy is outdated by 10 years.

It’s Not Just About Metro

It’s not just about you, Metro OEM. You and many other emergency managers around the country are fighting politics, budgets, and rapidly evolving population centers. We are singling you out here, yes, but this hasn’t been just a Metro problem.

Here’s a sampling over the years.

2010 City of Franklin

I would like to hear someone explain why Franklin sounded the tornado siren tonight. The city was well outside the Warning polygon.

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) October 25, 2010

2011 City of Franklin

The last three times Franklin has hit the siren it's been either too late or without an accompanying warning.

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) February 25, 2011

The siren is sounding in Franklin, but the NWS has EXCLUDED Franklin from the Warned Area.

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) May 2, 2011

2013 City of Franklin

For no good reason at all I'm hearing a tornado siren in Franklin. The threat in Franklin and everywhere else in both counties is OVER

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) January 30, 2013

There are NO Tornado Warnings in Davidson or Williamson Co. If you hear a siren, I don't know what to tell you.

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) November 18, 2013

A few Twitter *cough* exchanges between us and the City of Franklin prompted them to change their policy and only sound the City’s sirens when included inside the warning polygon. Williamson county (outside Franklin or Brentwood) uses a zoned system (if the polygon covers any part of a smaller “zone,” the sirens go off). It’s not perfect, but that zoned system is preferable to Metro’s all-or-nothing.

The problem continues today:

Our siren policy drives me crazy. Warning canceled. They should not be sounding now, also should not sound outside the warning polygon.

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) September 1, 2017

The weather enterprise is full of great people, but we have got to do a better job. A wailing siren should not contradict a warning polygon. pic.twitter.com/RwyolT0nPt

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) March 27, 2017

If wishing made it so, Davidson Co would have a tornado siren system communicating the same message as the NWS. https://t.co/HqmwWZg9l7

— NashSevereWx (@NashSevereWx) March 31, 2016

Metro’s sirens go off (1) where there is no warning and (2) frequently sound after the warning has expired and the threat has ended.

Siren Fatigue is Dangerous

Siren Fatigue means you hear the siren so much that you don’t immediately take life or property-saving action. Instead, you spend that time trying to see if the alert is legit, or, having been burned too many times by a false alarm, you ignore the warning altogether and go about your day, subjecting yourself to additional danger.

In 2013, smart guys Brotzge and Donner published The Tornado Warning Process: A Review of Current Research, Challenges, and Opportunities in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (Vol. 94: , Issue. 11, : Pages. 1715-1733). They concluded “…older warning systems, such as outdoor sirens, must still play a critical role within an integrated warning system, even as new, more informative services are made available.”

Brotzge and Donner cited this alarming study: False alarms increase injuries and fatalities. A study by Simmons and Sutter (2009, p. 38) found

“a one-standard-deviation increase in the false-alarm ratio increases expected fatalities by between 12% and 29% and increases expected injuries by between 14% and 32%.”

Real world examples underline the Siren Fatigue problem.

Joplin, Missouri

“‘The vast majority of Joplin residents’ did not respond to the first siren warning of the May 22 [2011] twister that killed 162 people because of a widespread disregard for tornado sirens, federal officials concluded in a report issued Tuesday. . . Officials didn’t blame residents, many of whom complained that sirens often go off in Joplin for tests or even just when dark clouds form, and suggested that a ‘non-routine warning mechanism’ be developed to make it clear when a siren should be taken seriously.” Read the full story here.

The vast majority didn’t respond.

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Oklahoma City changed its tornado siren policy in 2016 so that their new message to the public is “that when they hear a tornado siren this spring, it’s time to take shelter,” not go and try to find more information or ignore it altogether.

“Under [Oklahoma City’s] new tornado policy, sirens will only sound in parts of the city where a tornado threat exists rather than city-wide. The change means that residents who hear a tornado siren are in immediate danger,” said Lt. Frank Barnes, the city’s emergency manager.

“Because the old warnings were so broad, many people either complained about being warned unnecessarily or ignored the sirens, Barnes said. . . It was very clear that they did not like the county-based warnings that they were getting and they wanted a more localized warning,” Barnes said.

“That change is meant to cut down on unnecessary warnings,” Barnes said. “Oklahoma City covers 620 square miles, so it’s not often that the entire city is under a tornado threat. Under the old system, if a tornado warning was issued for southern Oklahoma City and Moore, people miles away in northern Oklahoma City would hear a siren, even though they weren’t under any threat.”

The Economic Argument

Reducing the size of the warned area saves money by not interrupting commerce.

“The warning forecaster strives to warn on every tornado, with as much lead time as possible, while minimizing the number of false alarm warnings. Having every tornado warned is essential for public safety; the public is much more likely to take shelter once they have received an official warning (Balluz et al. 2000). However, there is an incentive to keep the warning area size small; the use of smaller warning polygons is estimated to save over $1.9 billion annually in reduced interruption and unnecessary sheltering (Sutter and Erickson 2010). County-based tornado warnings were replaced with storm-based warning polygons in 2007.”

(Brotzge and Donner, The Tornado Warning Process: A Review of Current Research, Challenges, and Opportunities, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society Vol. 94: , Issue. 11, : Pages. 1715-1733).

Makes sense, right? If I don’t need to be taking cover, I could be working, learning, playing, whatever.

So let’s talk about our latest tornado day and the problems it presented to the NWS (they issue warnings) and to Metro (they activate its sirens).

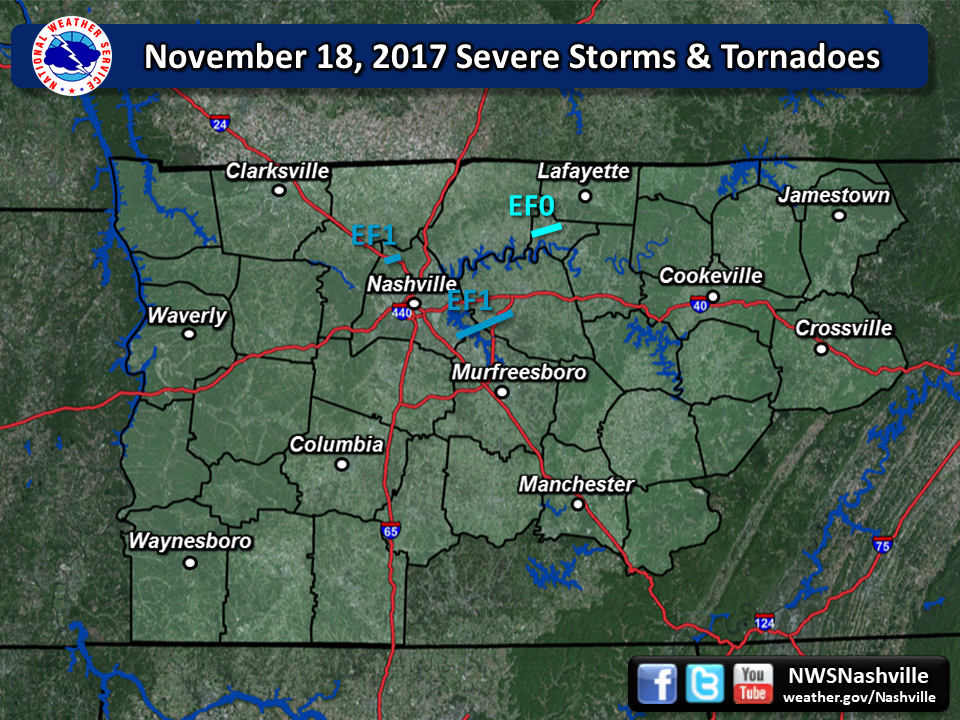

Our November 18, 2017 Tornadoes

There were two tornadoes in Davidson County.

The QLCS Tornado Problem

The tornadoes discussed below were embedded inside a squall line. Meteorologists call these storm lines QLCS, for quasi-linear convective systems. QLCS tornadoes can form anywhere inside the line and are often difficult to identify on radar; they’re different from supercell tornadoes where tornado detection is easier. Warning QLCS tornadoes is a big challenge for on-duty meteorologists. QLCS tornadoes are generally weak, short lived, they move linearly (they don’t wander), and may occur in between radar scans and thus never detected by radar. This is the next problem the science needs to tackle.

The Joelton Tornado

The first tornado touched down in Joelton in northwest Davidson County at 4:29 PM as an EF-0, with damage mostly to trees. It then crossed I-24 as an EF-1 tornado with 105 MPH winds, causing roof and power pole damage, but no injuries. The Joelton tornado lasted 4 minutes and traveled 2.25 miles.

Before the Joelton tornado touched down, the NWS office in Nashville issued a Severe Thunderstorm Warning with the qualification “tornado possible” in the text of the warning. No Tornado Warning was issued for the Joelton tornado, so Metro never activated its sirens.

The Gladeville Tornado

A second tornado (the “Gladeville” tornado) formed 19 minutes after the Joelton tornado ended, this time in extreme southeastern Davidson County near Percy Priest Lake, coming out of a different part of the line of the Joelton tornado. While in Davidson County, the tornado was weak, rated EF-0 (Will and I drove out there the next day). After a minute or so it crossed the lake and entered northwest Rutherford County, then streaked east-northeast and away from Davidson County into Wilson County, where it intensified into an EF-1 tornado and struck the town of Gladeville with 100 MPH winds, snapping trees and destroying outbuildings. Thankfully, there were no injuries.

The Gladeville tornado was tornado-warned. NWS-Nashville timely issued a Tornado Warning for Davidson County, Rutherford County, and Wilson County. Unlike the Joelton tornado, the Gladeville tornado was clearly seen on radar, with rotation discernible via velocity data, co-located with a debris signature. The tornado was in Davidson County only a few minutes. (For a more complete review of these tornadoes, see our assessment).

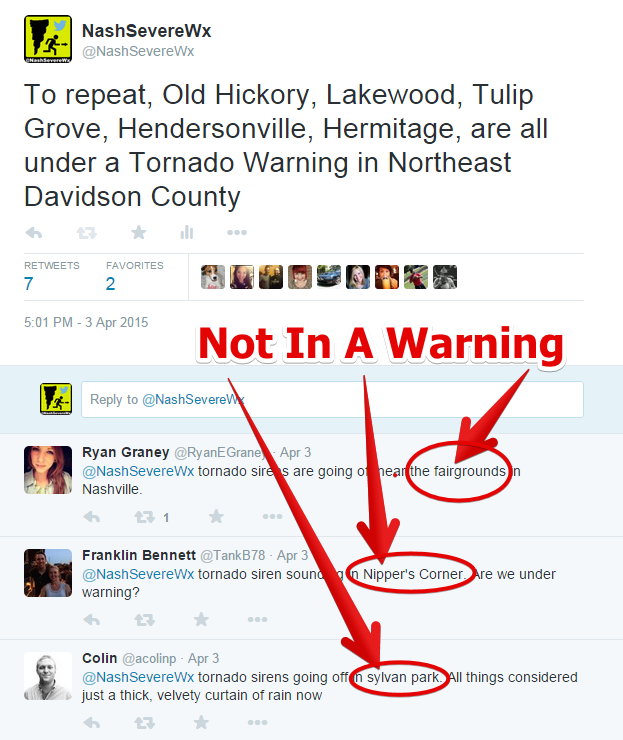

Consistent with its policy, Davidson County OEM sounded all of its 93 sirens for the Gladeville tornado. Of those 93 sirens, only 3 were close to the tornado in Davidson County. The remaining 90 tornado sirens alerted those outside the danger of this particular storm’s NWS-issued tornado warning polygon, effectively sounding an alarm to 98% of the county while they were outside the path of the storm.

These sirens not only falsely alarmed the majority of the people in the county in a geographic sense, but they also alerted 100% of the population longer than necessary, sounding long after the storm left Davidson County and was clearly in Rutherford County, then Wilson County.

Yet another example of overwarning. Another incident of Siren Fatigue.

Complaints by the public, including councilman Dave Rosenberg, prompted media inquiry, an OEM response, and the Mayor’s office promising a review.

The “Irregular Movement of Tornadoes” Justification

In its November 21, 2017 press release, Metro justified its activation of “all of Davidson County tornado sirens because of the irregular movement of tornadoes.” Metro apparently trusts the NWS enough to wait to sound its sirens until a tornado warning is issued, but they don’t trust them draw the warning polygon big enough, fearing the tornado may wander out of the polygon.

OEM should be — and is hereby challenged to — identify cases of QLCS tornadoes moving “irregularly” and out of the polygon and into an unwarned part of Davidson (or any other) County. This certainly did not happen November 18, or any other time we know of.

There was no way either of the QLCS tornadoes were going to wander out of their polygon.

Scholarship and peer reviewed science proves this “irregular movement” concern isn’t an actual problem. Speheger and Smith published an article in December 2006 On the Imprecision of Radar Signature Locations and Storm Path Forecasts. They concluded that “although precise, street-level locations of tornadoes cannot be determined, [tornado warning] polygons should be drawn to account for any error in radar interpretation or changes storm directions. If a tornado is suspected of developing outside its polygon, a new warning is issued.” That’s why the polygons are drawn as large as they are. It’s why warnings are frequently issued and updated.

Speheger and Smith were prophetic. In one case, radar software failed to pinpoint the exact location of the killer EF-4 Tuscaloosa tornado on April 27, 2011. That software plotted the tornado a few miles from where it actually was yet — and this important — the tornado stayed inside the polygon. The potential for error was accounted for by the size of the polygon.

Metro’s “irregular movement” argument is meritless and otherwise unsupported by science. Neither Speheger and Smith, nor any other scientist or social scientist we can find, advocates for a county-wide tornado siren system to account for “the irregular movement of tornadoes.”

The “Better Safe Than Sorry” Argument

Answering for the events of November 18, OEM told Davis Nolan “Our citizen safety is our No. 1 priority,” he said. “So, anything we can do to better the system we’re going to look at that. I would rather alert than get hurt and to let everyone know that there is a significant weather event happening in Davidson County.”

When I first hear that I stopped cold. Wait. What? Is the policy to only warn when NWS issues a tornado warning, or is the policy to warn when “there is a significant weather event?” Which is it? OEM’s departure from policy only caused more confusion to those watching Davis Nolan.

“Alert rather than get hurt” or “better safe than sorry” policy ignores the damaging impact of the overwarning/Siren Fatigue problem, discussed above.

NWS recognized the danger of overwarning, so it changed the entire way it issues storm warnings more than 10 years ago.

Studies confirm the intuitive: the more you sound a false alarm, the less effective the alarm becomes.

Oklahoma City recognized this. They changed their siren policy and fixed its overwarning/Siren Fatigue problem.

The City of Franklin changed.

It’s time for Metro to confront its outdated policy and grapple with what actually happens when the sirens say one thing, and everyone else says something else:

- A confused public, in a moment of high stress, wonders what to do next.

- They turn to TV media, social media, and the NWS, hoping someone has anticipated and resolves their confusion about whether they should be taking cover. Those in the path of the storm waste time trying to figure out if they are actually warned. Those outside the warning polygon either take cover unnecessarily or ignore the warning altogether, and are more likely to delay their response next time.

- The task of unraveling the confusion falls on local media and the NWS at the worst possible time, taking away time better spent staying ahead of the storm.

One Voice

“We want everyone on alert in Davidson County,” says the OEM press release. Instead of alert, we have confusion and complacency. Instead of action, we have people wasting precious time seeking secondary confirmation before sheltering, or simply ignoring the warning altogether. We have two voices, not one.

Tornadoes posing the greatest threat to life and property are often unmistakeable on radar. In the event we have one of these in Metro, we need clarity of message. We don’t need a population conditioned to seek confirmation when they need to seek shelter. We certainly don’t want anyone so desensitized to unnecessary over-warning to endanger their life because they’ve been ignoring the sirens and other warnings.

Here’s a small sampling of the harm caused by Metro’s policy.

Confusion:

Beyond the confusion, there is evidence the public ignores the sirens. Here’s a recent tweet:

I definitely ignore sirens, too, and come to your Twitter for reliable information. Our siren system is boy who cried wolf :/

— Lizzie Laster (@lizzielaster) September 2, 2017

Another one:

Seriously… we were in @MckayNashville at the time and not a single person cared that the sirens were going off. They're completely unreliable. Everyone just checks @NashSevereWx if things get bad. https://t.co/5EFiuisrJ0

— Ben McIntyre (@BenRMcIntyre) November 30, 2017

“Not a single person cared that sirens were going off” is very concerning. I can see it prompting you to get further information, but ignoring sirens altogether is not what we want, and it’s not what OEM wants, either.

The sirens should be part of the warning system instead of pulling against it.

Change on the Way?

“Anything we can do to better the system we’re going to look at that.”

That’s a quote from Metro OEM. I think it’s fair to ask what study supports the status quo? Where’s the social science supporting Metro’s “alert rather than get hurt” policy? Is the study from Joplin wrong? Is OKC wrong? Are the above-quoted studies error? Has NWS’s move to storm based warnings been a failure for 10 years? Is OEM’s rationale documented anywhere? Have they commissioned a study to find out?

According to the Scene, “Erik Cole, chief of Metro’s Office of Resilience, tells the Scene that the Barry administration has ‘asked OEM to substantiate what they feel the safest policy overall is and, further, what the options are (and related costs) for any system changes.’

‘In addition,” Cole adds in an email, “they have offered to review the plans of adjacent counties/localities and report back to us their findings. Finally, we are reaching out to our 100 Resilient Cities network to determine a cross section of best practices from other U.S. cities.’”

Here’s Mayor Barry’s tweet:

Hello – Mayor Barry and our office will be comprehensively reviewing our current storm warning siren system to determine if adjustments can be made in a cost-effective manner while still encouraging resident safety.

— Megan Barry (@MeganCBarry) November 20, 2017

And it appears she is making good on it.

I’m Not the Lone Voice

All four chief meteorologists agree the current siren policy has real problems.

Lisa Spencer:

This is great news…sirens going off for areas not under a tornado warning has been a problem for years. https://t.co/sfp1WNfZSC

— Lisa Spencer (@LisaSpencerWSMV) November 20, 2017

Bree Smith:

— Bree Sunshine Smith ☀️ (@BreeSmithWx) November 20, 2017

Danielle Breezy:

We are too! I am very happy about this! 🙂

— Danielle Breezy (@DanielleBreezy) November 20, 2017

Katy Morgan:

100% yes. https://t.co/oVlaC3yUce

— Katy Morgan (@katymorganwx) November 20, 2017

I hope the Mayor’s office will take time hear from all four Chiefs and other dissenting opinions.

I hope the Mayor’s office will demand studies justifying continuing the current policy.

I hope the Mayor’s office will pursue the best science, or even commission a study, to determine what to do next.

This has gone on too long. Let’s fix it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.