(I first wrote this on the 10 Year Anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. I revise it a bit every year for grammar and style, and based on how I’m feeling about it. –David)

I used to only love the weather: its science, uncertainty, power, beauty. I still love it but – real talk – I also hate it because it hits me in the feels, the personal feels, to see what it does to us.

Beneath the radar, happening under the satellite images, below the yellow and orange and red and other colored advisories, watches, and warnings, are people.

Poor people. Rich people. Those who don’t speak English. The elderly. The uninformed. The stubborn. The idiots. The innocent. The kids. The sick. All people – despite what you read on the cesspool of Twitter – are all equally and immeasurably valuable. For me, with Katrina, those people were Brandon and Wayne and Jennifer and Jason and Leslie and Ruben and Jon and Jon’s parents and the Wells and the Conners and the kid you could buy weed from and the coach I ejected from a little league game and Ozell’s family, I can go on and on.

For those on the coast, there is life before Katrina, and life after. For some of them, there was life before Katrina, and nothing else after.

Katrina doesn’t get to be personified. Katrina isn’t a “she.” Katrina is not a person, because if it was, I’d call it something else. Katrina was an “it.” It landed on the lives of all these people.

One week before Katrina came ashore, Katrina wasn’t yet Katrina. It was an unnamed, loosely organized “wave” in the Caribbean, a bunch of clouds about to start to tighten and rotate counter-clockwise, maturing from “disturbance” to “depression” to “tropical storm” to “hurricane” to “major hurricane.” A massive heat engine carrying ignorant wind and too much water. It wasn’t the concentrated Cat Five buzz saw called Camille in 1969 that tore up a part of the coast then did irreparable harm with inland flooding.

Katrina was The Hurricane of my generation.

Katrina was a meteorological wonder. Two parts marvel and wonder at its size and strength, two million parts chaos, tragedy, and mess. It was all so gradual, and all so sudden. You have to stand in the debris to know that.

Katrina was personal and emotional for me, but I did not suffer real loss. I went to high school on the Coast, first in Pass Christian, then in Gulfport, where I graduated in 1994. But I wasn’t there for it. I’d been here in Tennessee for several years before Katrina came ashore. Katrina hit me in the memories, where my sister and I went to school, where dad worked, where mom worked as an immunization nurse. It tore up Bay St. Louis, Pass Christian and Long Beach, Gulfport, and Biloxi.

If designing a hurricane to do maximum damage to Mississippi, I would not change much from this radar loop, showing how Katrina came ashore:

It made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane on a Sunday night, with the strongest part of the storm — that awful northeast quadrant — landing squarely on the Mississippi Coast:

I was at home here, watching, concerned, as it powered ashore. I remember where I stood in my bedroom while watching the infrared images on TV. Looking back on it, I was growing quietly upset inside, but I was not as alarmed as I probably should have been. That Sunday night, I just didn’t know. Nobody did. I hadn’t yet seen it. I hadn’t stood in it.

As the news caught up about what had happened to New Orleans and Mississippi, what was left of Katrina arrived here in Tennessee. We got a lot of rain, some high winds, downed trees, power outages, and — most importantly — no deaths. For us, when Katrina left, life returned right back to normal.

Mississippi was torn up. 10 days after landfall, when there was gas to get there, I was on a bus with some of you, on my way to Biloxi to help out, and to see it all for myself.

Dozens of y’all were on that bus with me, transporting water and equipment and lots of other stuff. I brought a chain saw I didn’t know how to use. I packed my dad’s work boots. We see someone in trouble, we volunteer, what else is there to think about?

Our bus drove south down I-65, into Alabama, which would have its generational weather tragedy six years later on April 15 and April 27, 2011.

We crossed west out of Alabama and into Mississippi.

When we took I-57 and turned south just after Meridian, you started to notice the trees.

Trees were standing, but no tree stood straight up. These trees were 100 miles from the coast but they leaned away, bent north and in unison, like a concert crowd swaying a ballad.

The longer we drove south, the steeper the tree lean. Lean became bend, and as we got even closer to the coast, bend became break.

First small trees broken (the photo below shows after Katrina : before Katrina) . . .

. . . then, further south, big trees had fallen, either snapped, or its roots unable to hold it and down it had gone. Awe became alarm as I looked out the window. What were we driving in to?

I became quiet. I did not see or hear anyone else. I suppose I was trying to process. I knew the people down there, I had memories down there, and I was afraid of what I was going to see. Familiar things were no longer the same.

We got there. It was not the place I knew.

It wasn’t just changed, it was different. The entire coast was put in a blender.

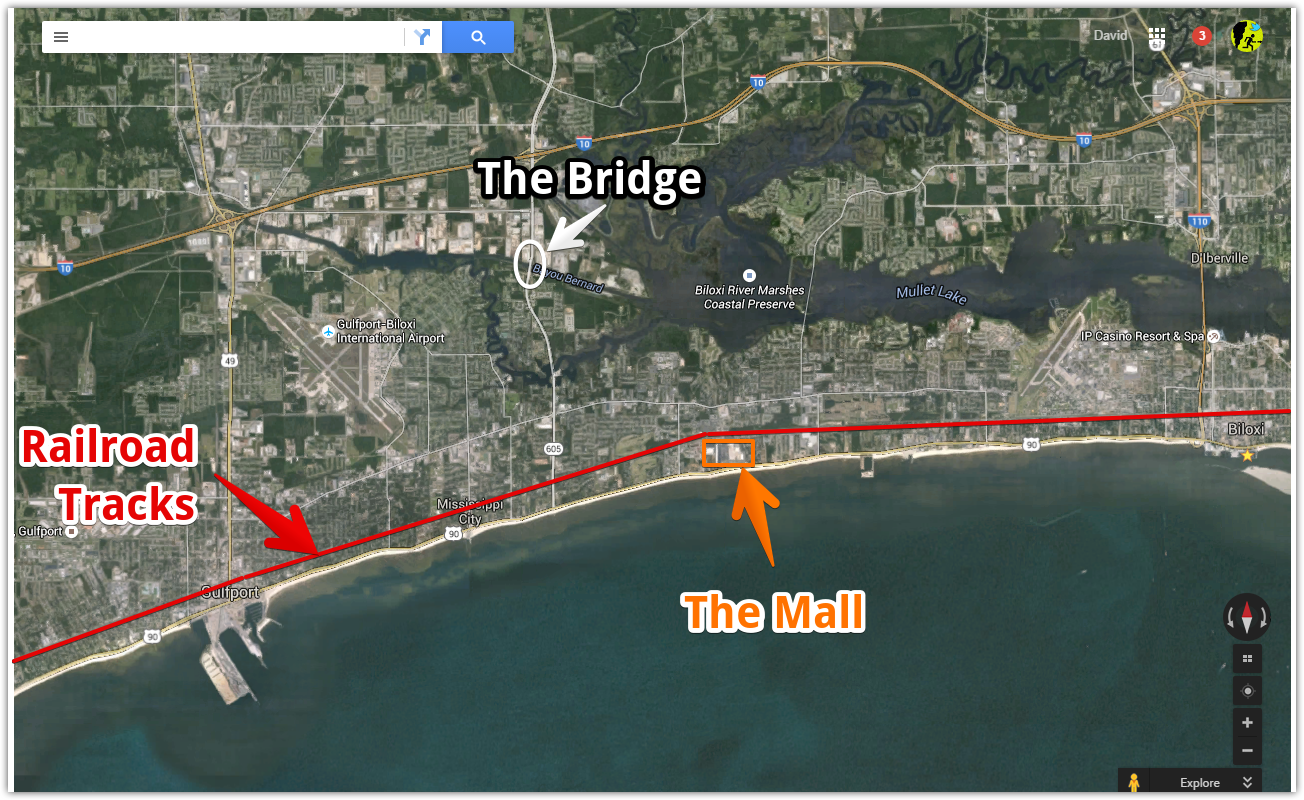

We crossed one Gulfport bridge that spanned over a bayou where I had been sometimes invited to ski with people from church (actually, kneeboard, very badly). This bayou was maybe forty yards wide, located a few miles north of the shore. This bayou is a narrow, deep channel, wide enough for small to medium sized boats and not much else. Locals trying to save their boats “parked” them in the bayou, dropped anchor, thinking the distance from the shoreline would provide shelter from Katrina.

The bayou provided no shelter. Katrina rose the water, the bayou flooded its banks, and the wind did the rest. It was like taking matchbox cars on a made bed, lifting then shaking the sheets, earthquaking everything on it. Some boats landed as if they’d been thrown. When the bayou receded into its banks, the boats weren’t on the water. They were on land, or jammed onto the side of the banks, busted up, sideways, sunk, upside down, strewn matchbox cars now abandoned to be dealt with later. This is what we saw as we drove into town.

Trees lost their leaves. Leaves were supposed to still be on the trees. It was such a strange scene, it being really hot, really humid, without leaves on the trees.

Blue tarps served as temporary roofs, smurfing houses and businesses still standing.

It was still hot, exceptionally humid. Post hurricane humidity is cruel, making work difficult for those dragging trees to curbs, restoring power, digging out molded, mildewing carpet, constructing huge piles of debris for “the trash” to come pickup.

We drove straight to the beach, across the railroad tracks which run parallel to the water, then to what was (and today still is) Edgewater Mall. The Mall looks over the water, and if you’ve never been there, you should know the water is not the Gulf of Mexico. It’s actually the waveless Mississippi Sound. The Gulf is a few miles out, on the other side of thin, worthless “barrier” islands.

We pulled in to the parking lot of Edgewater Mall. One hundred or so power company trucks were parked there, surrounded by skeletoned strip-mall style now-former shops. An ice-cream place where my sister used to work. Restaurants, a record store, the baseball card shop I frequented in high school, fast food, stuff like that.

All that was left of these shops were steel beams and facade and a few walls and rotting, saltwater drenched wood and drywall, with mildewing carpet.

You could look straight through some of the shops; what a strange thing, looking through them. Sunlight on the other side. The storm surge had been here.

I stood in this lot, hands on the back of my head:

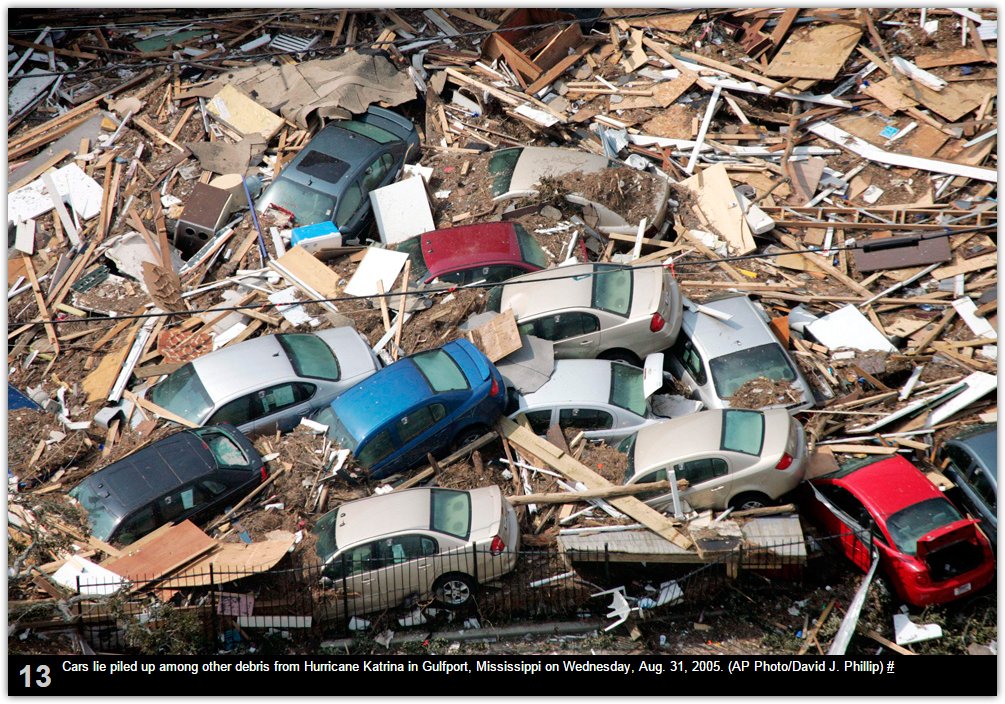

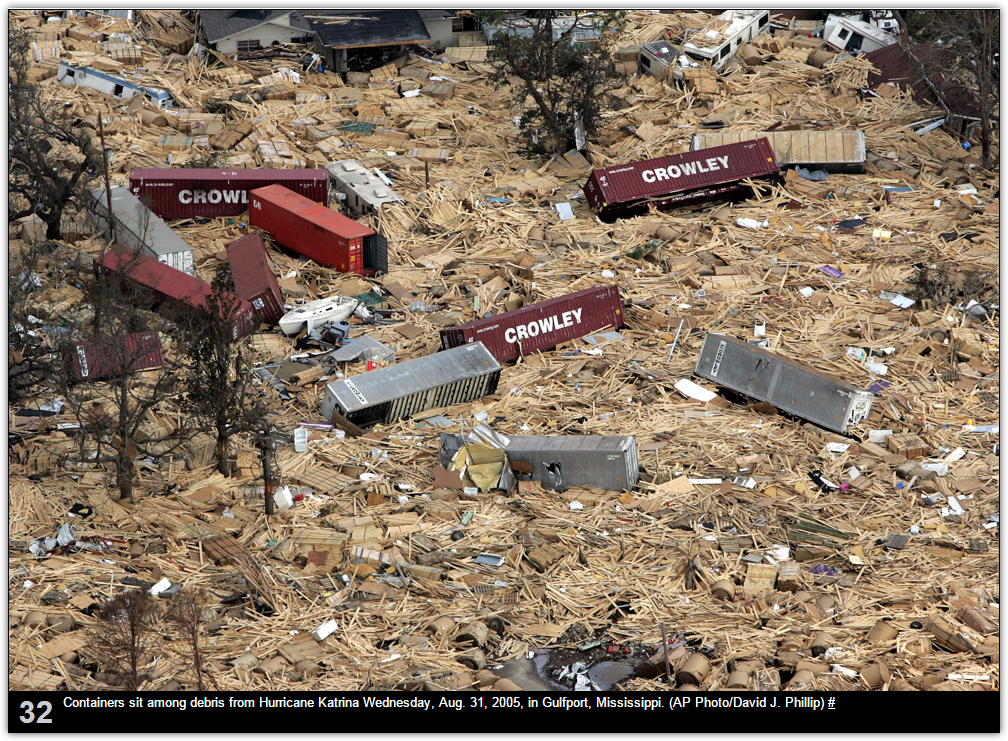

Further down the shoreline, debarked trees were everywhere. There were Giant Piles of lumber, shingles, weeds, trees, cars, earth, some piles holding bodies of people and pets, other piles of medicine people need, photos that could not be replaced. Houses, businesses, condos, and motels and the furniture and piping and papers they held, mixed together, had been destroyed and rubblized, shoved northwest by the storm surge toward the railroad tracks where it piled up, then some of it dragged back out into the Mississippi Sound when the water receded, the rest of it left to sit there to dry out in the stifling heat and humidity. Concrete slabs held debris from a different street or adjacent neighborhood.

The wind was strong, but the water did this.

I mean, look at this photo.

That’s not debris pushed into a pile or scattered on a hill. That’s a pile of debris. “The pile of debris” what we used to call the Isle of Capri Casino, a phrase we thought was funny at the time, but, standing there, the Isle of Capri Casino was an actual pile of debris and nothing about it was funny.

Standing there was like waking up in a hotel in a strange city and not knowing exactly where you are.

After some time standing in that Edgewater Mall parking lot for I don’t know how long, I realized everyone else was back on the bus, kindly waiting for me. No one had wanted to bother me. No one else on my bus was from Gulfport. I got back on the bus. There was so much to do. So much.

And it was just so sad and overwhelming and it did something to me that day and maybe that’s why I tweet the weather here in Nashville.

We left the Mall area. We met up at a church, where cool stuff was happening. This was a small church on Pass Road, where, we were told later, the preacher had recently preached about the feeding of the 5,000. We got there to find a church transformed into a small, buzzing, whirring relief hub, feeding and supplying God knows how many thousand residents, and supporting the basic needs of volunteers from NYC, Wisconsin, New Jersey, Missouri, North Carolina, and yeah, us too. We aren’t the only Volunteer State.

The chainsaw I didn’t know how to use and no one could get to work was the reason I was asked/told to go with a chainsaw crew the next morning. I was a “local,” because I lived there and knew how to get around, Or, at least I thought I did.

I wasn’t a real local. I was a former local. I had an emotional stake but no future stake in this mess. None of my stuff was in a pile or sitting in the Mississippi Sound. My job wasn’t gone. In four days I was going to leave there and my community here in Tennessee would be the same. I think about that even today, the relief is great and necessary and So Very Much Needed, but the real work comes in the days and weeks and months and years later.

Over the next four days, I navigated – but certainly did not lead, that’s another story – a crew of men to the homes of elderly and disabled residents that came from a list the church gave us. On several occasions I had to try and get a phone line and call my dad to talk through how to get exactly where we needed to go because the landmarks used for navigation were gone, or roads were closed and I needed to find another way, or the names on the concrete road posts common to the Coast were faded or obstructed. There was no Google Maps. We pulled carpet, cleared land, cut down more trees than I could count, and did whatever else we could do for people either unable to help themselves, or too overwhelmed to get to what they needed to do, or both.

There was no one else there willing or able to do it. The relief effort was substantial. The need was massive.

In a crisis of this magnitude, as many of us in Nashville unfortunately know, survivors are the first responders. Then come volunteers.

Then comes the government.

Men in FEMA polos showed up at the church to suggest we didn’t have the permits or whatever to do what we were doing. They were politely ignored, and they let us be. By the end of my time there, FEMA returned and asked us for water and other supplies, which we had because eighteen wheelers from all over the country packed with essential items, and driven by men and women who left their homes without knowing exactly know where to go, had been driving and arriving all day and night, ending up at this small church on Pass Road on the Biloxi side of the Gulfport-Biloxi line. These trucks met all immediate needs. Locals came by to pick up water and toiletries and clothes and whatever the trucks brought, drive-thru style. There was order in the chaos, and way more than 5,000 were fed.

One day, some guy showed up driving a pickup truck packed with supplies he gathered from friends and family in St. Louis. He had so much stuff to bring, he built an extension atop the back of his truck to hold it all. He came with his dog. He wanted to help, but he didn’t know how, or where he was going. He just drove south. He wanted to bring the stuff to the people, so together we went, just the two of us, to try and get stuff from his truck to people who couldn’t get to the church. He had the stuff and I knew where the people were. The poorest. The most vulnerable.

I showed him the back roads and the “forgotten” areas of the coast, and we delivered stuff. Bottled water. Coloring books and crayons. Clothes. Toothpaste. Food. The last morning we were there, a Sunday, by then two weeks removed from Katrina, he gave me his keys because he wanted to stay to help fix the church roof, but he wanted his truck in use and emptied and I wanted to get away from the church and do something, so I took the truck myself. It was stupid for me to go alone, so after running into a friend of a friend I had gone to college with, the two of us drove all over Gulfport, distributing supplies to churches and homes and apartments and other places still standing. We saw people living in places like this:

The people who stayed through the storm, and survived, were tired and scared. Their kids were 2 parts awed, 20 parts scared, 200 parts exhausted, and 2,000 parts confused.

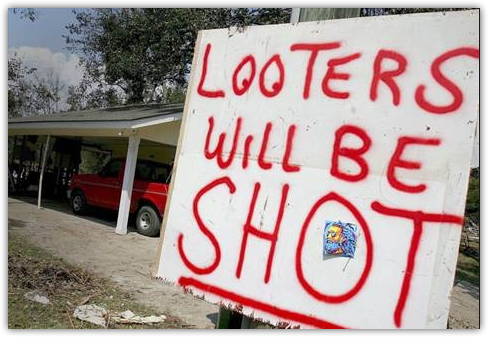

They were justifiably leery of price gougers and looters and run of the mill criminals looking to prey. There was racial tension, there was confrontation, there were guns, and there was an after-dark curfew.

Most let us come close. A few didn’t, one motioning to a gun in his waistline, but most people wanted to talk, to tell someone not from there what had happened to them, and what was happening to them. They wanted to be heard, to know someone cared.

We found people with no tools to clear their yards and no medicine to treat their sick and no toys to occupy their kids and some with no shoes to really go anywhere and no water to keep from passing out due to the heat and humidity. The ground was full of sand and grass and hidden nails, everything had a splinter, shingles everywhere. Flat tires were a problem. Wildlife had been displaced and was in places it shouldn’t have been. Snakes, gators, rodents. For many, and especially the poor, their medicine and toys and beds and tools and shoes and cars were debris, debris they couldn’t get to, and even if they could, it wasn’t salvageable.

As always, those most impacted were least able to cope.

Those who didn’t suffer total loss had water damage. Most of their clothes were ruined. Carpets and carpet pads needed stripping.

If you were poor, you were poorer. If you had pride, you were humbled.

Those with jobs didn’t have a way to get to work or a job to go to. Photos and diplomas and jewelry were waterlogged or mixed into the rubble, but none of that was on the forefront of their minds. Those with houses standing were more concerned about mold and mildew. They wondered about insurance claims. When would the money come? Would the money come?

As we drove, it was hot, still, and stifling, the humidity blanket thick and unrelenting. Most people had no option but to move. How could they stay? There were no jobs here, and it wasn’t healthy to stay in a wet, mildewy, moldy house.

My capacity to be selfish and curious remained. I wanted to get to the first house we lived in when we moved to Gulfport in 1989. I wanted to know what would have happened to us had we been there. That house was small, a rental, at the beach, on Highway 90. I knew it and everything else around it was gone, but I wanted to see it to believe it. But I could not get to it. National Guard troops were stationed at the railroad tracks, which sit up on a levee-like rise, forbidding anyone to approach the two or three blocks of rubble between it and the beach. Such was the extent of the destruction.

But I had my answer. No house near the beach really survived Katrina.

The tallest debris piles were pushed on the south side of the tracks. All you could do was stand on the tracks and look at the debris and wonder how it could all be hauled away. Mostly, you hoped no one was in it.

On the south side of those tracks was the church I’d gone to . . .

. . . the library where I spent an unhealthy amount of time (the first floor was full of rows and rows of books, we had a great library) . . .

. . . the house where my family cared for foster kids and the place I got very sick and places we had birthdays and got our family dog and had our favorite Chinese food. It was where friends lived, where I played weeknight tennis against my dad, and the only place I ever really had gone fishing, where I learned to drive. There was a real sense of real loss seeing that stuff reduced to a pile. For as far as you could see. You could not revisit it anymore.

I heard first person trauma stories from folks who rode out the storm, who retreated inland and lost power and still were flooded, traumatized people coming to grips with their new reality.

One guy told me his story. He ignored all warnings. He stayed in his house which was swept away by the storm surge, with him in it. He climbed out and rode his roof, blown debris flying overhead. Yes, he was on top of his roof while it was floating atop the storm surge. He stayed low, keeping his head down as debris blew over his head. Eventually the water sat the roof down on a debris pile. He wasn’t sure how long he’d been on the roof. He picked his way through the rubble and walked away, having somehow escaped the consequences of his horrible decision. It was hard to believe his story, hard to believe he’d survived, and hard to call him a liar. Maybe he was telling the truth. I don’t know.

There is always exaggeration in tragedy, just as there are horrors never told.

I heard the story of another guy, on TV. I knew him. Responsible, respected, served in Vietnam. Doesn’t make stuff up. While in high school I worked for him as an umpire; I remembered one summer night the two of us crowded around a small concession stand TV after a baseball game that I worked and he scored and watched OJ and Al Cowlings in the slow white Bronco. During Katrina, he also ignored evacuation warnings. He stayed in his old, majestic, two story home, near the beach, south of the tracks. Katrina rose the water to his doorstep, the water forced itself inside, and flooded the first floor of his house. When it filled the entire first floor, he and his wife had no choice but to go upstairs. The water kept rising, to the second floor windows. Rising water meant they couldn’t stay in the house, so he belted himself to his wife and they swam out a second floor window, where they rode out the storm clinging to a tree.

Those are stories of survivors. We will never get the stories of others who decided to “ride it out.”

The “coast” community lost more than their stuff, their businesses, the people who the storm killed or who just moved away. They lost the sameness, the comforting familiarity of home. They could not go back to it. Two weeks after Katrina, the only thing that appeared the same on the coast was the Mississippi Sound. Just before I left to return home from our relief trip, the Mississippi Sound sat still, quiet, serene and smug, fat and fed, having ingested the Coast.

I don’t know why I keep telling this story. Maybe it’s therapy for me, I don’t know. I don’t want to turn this into a weather dude preachy thing about heeding warnings, or about the nightmares I still have about the things I saw down there. Mostly, I just want to say these disasters sledgehammer those least able to deal with them. It stirred things in me, and changed the way I look at the world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.